The place I made my first film just burned to the ground

Yesterday, the place where I made my first film burned to the ground. It was 2015 and, fresh out of my masters degree, I had begun fumbling my way into documentary filmmaking. I had the “wrong” camera and was going about it the “wrong” way, but I was having a crack. Through one connection […]

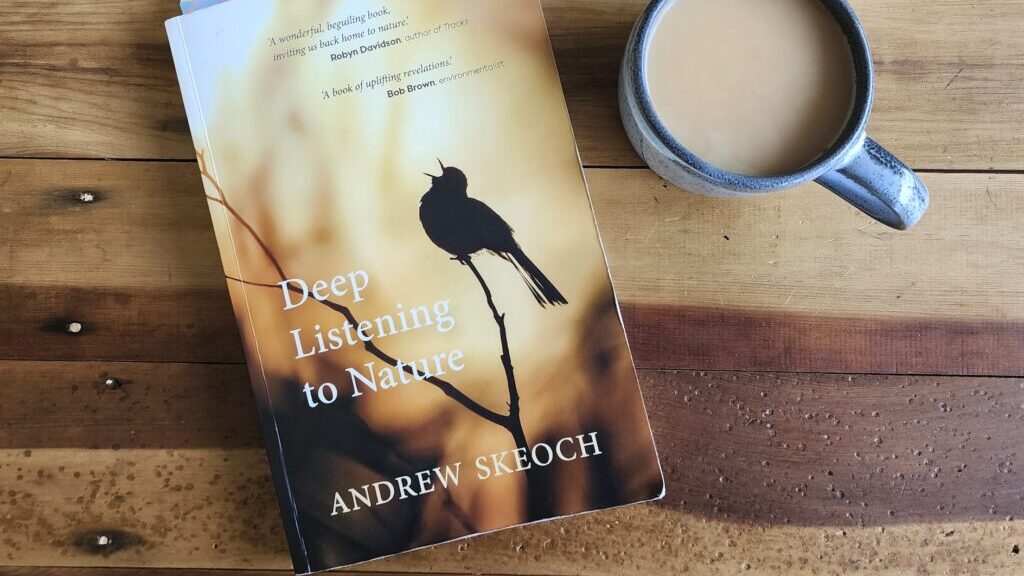

Learning to listen and listening to learn

Catherine Cavallo Articles, Feature Articles September 18, 2024 Catherine Cavallo September 18, 2024 I’m walking down into a gully on the lands of the Dja Dja Wurrung. It is a misty morning, the winter sun yet to burn off the dew of the night before. The bush is quiet, muted. But here and there I […]

Of bird nests and bench grinders

She and her mate are bush songsters. Their melodious whistling reverberates among the eucalypts each morning and reminds me, as I lie in bed, that I have come home….

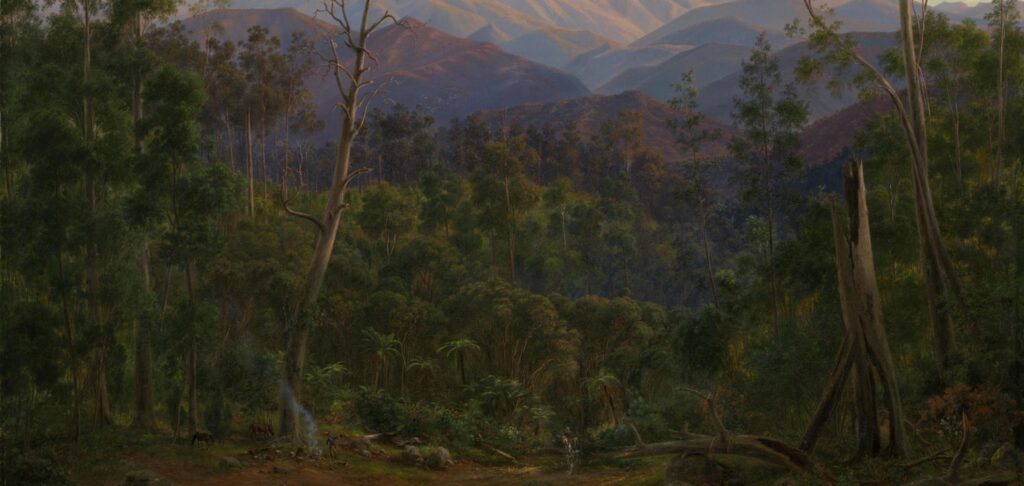

A glimpse into the past

When useful works of art are identified and verified, they can be invaluable tools for environmental rehabilitation…

Eucalypt mythbusting: a comprehensive guide

Misconceptions about eucalypts abound. They seem to be as widespread and diverse as the eucalypts themselves…